- The Cebuano Memoriam

- August 15, 2023

- Benjamin Manto

- visuals byGabriel C. Dizon, Mel Francis Amadora

“Imo sa oh!”

“Wa’y apelidohay!”

“Imna nana aron matuyok na ang baso.”

“Ayaw ipanihapon ang pulutan!”

“Gunner mao pay nahubog.”

Woven intricately into Visayan culture—tagay has become a cherished social and recreational activity of the Visayan (Cebuano) people where friends and family come together to enjoy alcoholic beverages at clubs and karaoke sessions. While it did not exist in the same manner in the past, the culture of drinking can be traced back to pre-colonial times, taking on different forms and cultural significance throughout history.

Tagay translates to “bottoms up” in Cebuano. Historically, this cordial gathering was exclusively attended by men for the shared purpose of honoring rituals and traditional ceremonies, sharing stories of valor—toasting to victories, and, most notably, as a symbolic representation of kinship and strengthening the bonds amongst colonizers. JL Piscos’ study in 2020 highlights three historical significance of “Tagay” to the Visayan people.

Firstly, it was used as a binding force in settling disputes with foreign invaders. When Magellan arrived at Zamal (Samar) on March 16, 1521, tensions escalated between the Spaniards and the locals. The situation was resolved amicably when the Spaniards offered various things such as combs, mirrors, bells and ivory. The Visayans reciprocated with fish and a vessel of palm wine. Consequently, eating and drinking came after and began strengthening their relationship of respect and understanding.

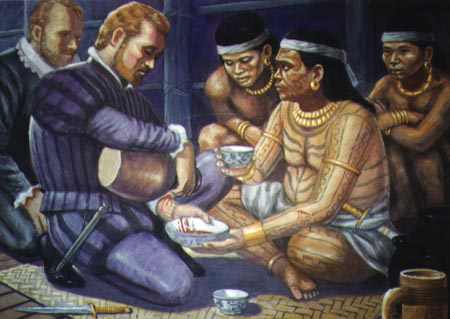

Tagay played a pivotal role in Miguel Lopez de Legazpi’s arrival in 1565. A momentous occurrence took place when Legazpi and Sikatuna, a Datu from Bohol, enacted a blood compact that solidified their new alliance. Both parties engaged in drinking and feasting, where the natives graciously offered their finest wine to the Spaniards, fortifying the union between the two cultures. Although tagay played a role in establishing peace and unity, it also gave the Visayans a way to resist the Spaniards without bloodshed as demonstrated by Rajah Humabon of Cebu, who poisoned several of Magellan’s troops over a meal together following the captain’s death (Pigafetta, 1522, as cited in Piscos, 2020).

Blood Compact ‘Sanduguan’ By Manuel Panares

Additionally, it is an integral part of social gatherings. During the Spanish contact in the 16th century, the Visayan society was divided into several social divisions; the Datu (chief leader), Timawa (freemen), and Oripun (slaves). Historically, only chiefs and commoners had the luxury of indulging in opulent beverages at their wedding rites, signifying the couple’s commitment and vow to support one another. Contrarily, the impoverished slaves lacked these rights and were unable to perform elaborate wedding rituals without ceremonial drinking like the Datus and the Timawas. It was also practiced during the first menstrual period for young girls, and rituals were done by the families to represent their fertility and wealth in life. According to Chirino (1603, as cited in Piscos, 2020), drinking among the Visayans is an intrinsic way of life. During non-mourning feasts, they engage in singing, playing instruments, and dancing, passionately spending days and nights until they end up falling asleep due to exhaustion.

Lastly, is its inclusion in the maganito tradition. According to Pigafetta (1522, as cited in Piscos, 2020), drinking is a significant component of the maganito ceremony, in which participants dance around a tied pig while priestesses recite incantations, distribute wine, and offer direct prayers to the sun. This leads to a tribute that promotes harmony and tranquility while tying the neighborhood to the anitos. In the Visayan tradition, the maganito ritual was centered on drinking and was performed prior to crop cultivation. The celebrations began with drinking, eating, and loud music, with women and young people dancing and ringing bells and playing various instruments, signifying a fertility ceremony that improved the community’s well-being (Boder Codex, 1593, as cited in Piscos, 2020).

Drinking also functions not only as a venue for storytelling but also for engaging in creative discussions. In the article by Alunan (2021) titled “Tagay-tagay Poetics and Gender in Cebuano Verse,” she thoroughly discussed and emphasized how the tagay tradition preserves oral Cebuano poetry, enabling literary conversations and giving aspiring writers a forum on which to improve their poetic abilities. Such poetic customs are honored during tagay gatherings and deliberately passed down from one generation to the next.

Are there any similarities you can think of in how tagay is practiced in today’s time?

Perhaps you have experienced the camaraderie of tagay gatherings, where you and your friends come together while singing Visayan songs with a guitar or karaoke. Maybe you engaged in drinking while discussing personal matters as you toast each other’s glasses, play cards while enjoying a drink, or playfully taunt some of your pals whose partners (lover) are asking them to go home.

In a blog post by Ligaya in 2012, she referenced the insights of historian William Henry Scott into ancient Visayan drinking culture. Before the emergence of the modern, luxurious wines we savor today, there were early versions of Visayan wine. The most popular local wine is known as Tuba—a fermented palm sap enriched with red-colored crushed tungog (tanbark) or lawaan tree bark. Pigafetta considered this beverage of superior strength and quality (Fernandez, 1987). On the milder variety is Lina, a sweetish sap without the addition of tungog, which is regarded to be the “ladies’ drink.” There was also a bitter-sour version of Tuba called Bahal, and elevating its strength would result in its robust brew called Lambanog, also known as Anisado when infused with anise seeds.

A kawa still for the production of Lambanog. source: http:www.wikipedia.org/wiki/tuba

Today tagay remains an intrinsic part of the Visayan (Cebuano) drinking culture. It can be seen in all types of formal and informal gatherings. Throughout time, it will always have a special place in Visayan’s hearts as they recount their personal stories and bring together the past and present in a toast to celebration and unity. It is a testament of pakig-hiusa (unity) where everyone is respected and valued, regardless of their status in life.

Cheers to history!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin Manto

23 | A Gemini Soul

- Ardent lover of cats

- ELS Student

- Agnostic