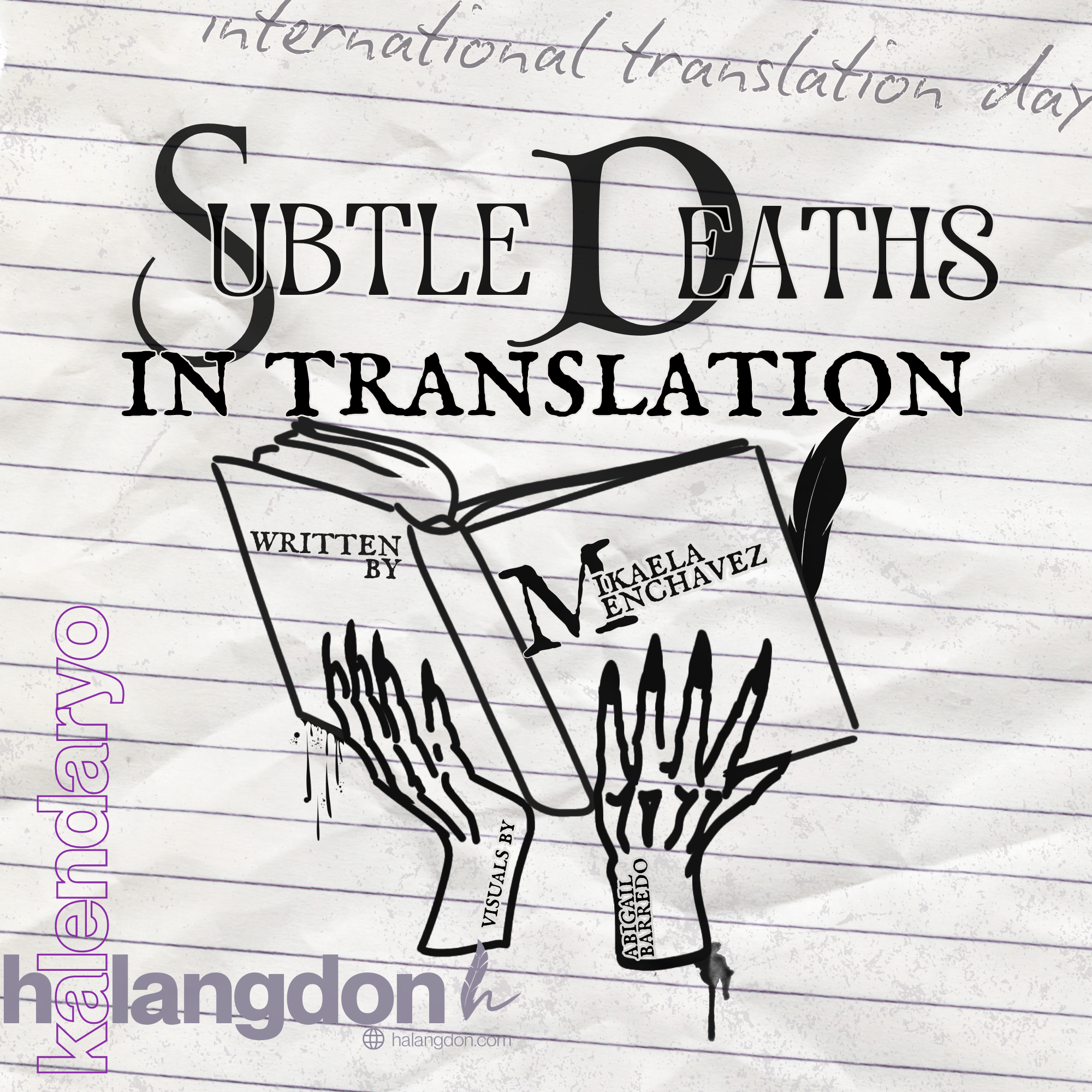

Deaths in

Translation

- Features

- September 30, 2024

- Mikaela Angela Menchavez

- visuals byAbigail Barredo

American novelist R.F. Kuang presented a thought in her novel Babel that has remained in my mind ever since the night that I first read it: “Translation means doing violence upon the original, it means warping and distorting it for foreign, unintended eyes. So, where does that leave us? How can we conclude except by acknowledging that an act of translation is always an act of betrayal?”

If what Kuang suggested is true and that the act of translation is truly an act of betrayal, then what does that make us—ignorant overconsumers of translation? With how accustomed our current generation is to the effects of globalization, it may be easy to overlook how often we encounter translated content in our daily lives. From the translated instructions on skin care products to the subtitles of our favorite foreign shows projected on our TV screens, translated material is incorporated into almost everything we interact with. It is much simpler to take advantage of the convenience we enjoy from the translations we consume daily.

Before we examine that, let’s discuss the act of translation first. In hindsight, translation is merely transforming text from one language into another. I use the term “merely transforming” quite loosely for there is nothing “mere” about transformation. We experience transformation in greater scales; the way toddlers turn into adults, when seasons change from summer to winter, and when world leaders decide to transition from a time of peace to gruesome wars. An act of transformation will never go unnoticed with the exception of translation, which is in most cases undervalued.

The translation as an act of betrayal evokes the question, “should we consider translation as a negative aspect of linguistic development?” Not at all. On the contrary, the conversion of languages from one to the other has made it all the more effortless to dismantle language barriers among different people around the globe. Moreover, with the emergence of translation and the revolutionary influence of technology, it has now become easier for individuals to become aware and interested in cultures different from their own, which has pioneered the avenue for more effective intercultural communication.

Do these benefits negate the definition of translation being an act of betrayal? Absolutely not. To understand this, let us shift our perspective and look at translation beyond just the act of interpreting one language into another.

The enigma that is language itself—let’s start there. Wouldn’t you agree that it is quite ironic that the complexities of language can not be summarized in the medium in which it is presented? Nonetheless, what we do know for certain is that language is integrated heavily into our cultural identity. To translate then would infer breaking apart one’s cultural identity—a part of the self—into tiny fragments to contort it and make it simpler for outsiders to understand.

To add to that, to translate is to give birth to a new set of words. While fragments of the original meaning might remain intact, the newborn word, phrase, sentence, or paragraph operates independently considering that it is something intended only for the comprehension of those who do not enjoy the privilege of understanding the primary language of which the translation is derived from. Furthermore, it is a known fact that no translation of any script is ever a hundred percent accurate—why else would we consider words in our vernacular, “simbako” and “mirisi” among others, to be special if it doesn’t have an exact English equivalent?

Echoing what I mentioned before—to translate is to transform. To transform implies the existence of something broken. Most of the time, what is broken is the translator’s sense of self.

After all, what right does anyone have to prevent one from exercising their right to express themselves using the language of their motherland? This happens much more often than you think. For instance, the protagonist of Kuang’s Babel is battered down by being forced to think in a language that he does not own. Not only this, but he is abruptly shipped to a foreign land and taught language upon language, all the while slowly losing touch of his mother tongue. In the first chapter of the book, he is told by a man who wishes to invade his mind, “I know you have English. Use it,” which completely strips the main character of his autonomy, and, above all, his identity.

With all of that being said, the main point I intend to emphasize is that to translate is to undergo subtle, almost unnoticeable, deaths with every word metamorphosed. This leads us to the role of translators in our society. Oftentimes, they are overlooked and unrecognized. We, as ignorant overconsumers of translated media, usually fail to realize that in their line of work, translators have to undergo subtle deaths with every word they contort. Putting this into consideration, isn’t it an admirable skill to remain in touch with one’s mother tongue after having been exposed to a plethora of foreign languages?

Ultimately, translation is not just paraphrasing something in another language. Instead, it is transfiguring one’s script in the pursuit of interconnectedness, intimacy with outsiders, and the overall development of our global community. To set aside one’s cultural and linguistic pride for the betterment of the world—now isn’t that a noble cause? In this way, the act of translation is inherently selfless, as translators do not translate media for their own sake, but for the benefit of those who seek to understand foreign culture.

So the next time you search for the English translation of a K-pop song you like or when you finally decide to pick up that translated book from an Italian novelist, remember the translators who go through subtle, almost unnoticeable, deaths with every word and phrase they rewrite—especially today, which is International Translation Day!

By way of conclusion, the act of translation is an act of transformation, betrayal, rebirth, deconstruction, and selflessness. With how convoluted language is, I think all of these facets can co-exist and intermingle—much like all languages themselves.